Lecture 19

In-class notes: CS 505 Spring 2025 Lecture 19

Interactive Proofs

Recall the definition of NP with respect to deterministic Turing machines (i.e., verifiers). In some sense, the string is a “proof” that .

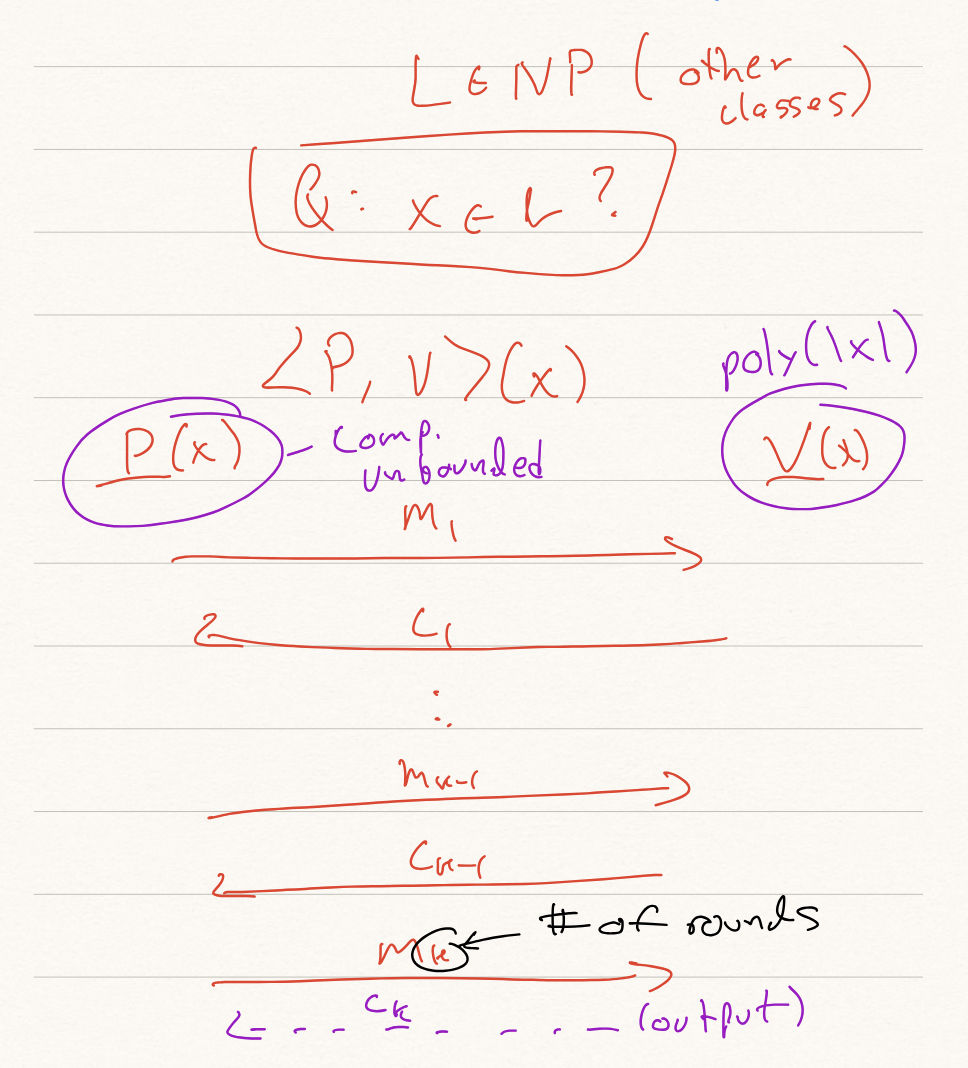

Interactive Proofs (IPs) were an attempt to re-define NP languages using interaction. Every IP is described by two interactive algorithms/Turing machines . For a given language (or other classes, as we will see), an IP seeks to answer/certify whether .

In an IP, the prover algorithm is assumed to be computationally unbounded; that is, it can perform any computation, even decide undecidable problems. However, we restrict the verifier to be strictly polynomial-time in the length of the input to the protocol . We restrict ourselves to the protocol format described in the above picture, where the protocol has rounds and has messages, where always sends the first and last message. Note that this model can capture when the verifier sends the first and last messages (the prover’s first and last messages are simply empty).

Every message of the prover is a function of the input and all prior messages sent in the protocol; i.e., . Similarly, the verifier messages are a function of the input and all prior messages received in the protocol; i.e., . The output of the protocol is denoted by , where is a private input that may receive, and is a private input that may receive, and is the common/public input that both parties receive. Note that in the case that and receive a private input, then the messages each party sends are also a function of these private inputs. The output is defined as , and is a bit indicating whether the verifier accepts the interaction (i.e., if should believe that is a true statement).

Note that because we are restricting the verifier to be strictly polynomial time, this naturally restricts the size of all to be at most bits.

Some natural questions come to mind with the above model.

- Should and be allowed to use randomness? We will address this question soon.

- What is an accepting or rejecting proof? We will also address this question soon.

- Who sends the first/last message? We discussed this briefly above; it doesn’t matter too much.

- What is the size of the proof? This is simply the total number of bits exchanged between both parties; by the above discussion, all proofs are bits.

Deterministic IPs

In this model, we restrict both the prover and the verifier to be deterministic.

Definition. We say that a language is in the class if there exists a -round ( message) IP such that for any , has the following properties:

- (Completeness) If , then .

- (Soundness) If , then for any algorithm , .

- (Rounds) The IP has rounds.

The class is defined as .

Unfortunately, deterministic IPs are no more powerful than NP.

Theorem. .

Proof.

-

. If , then there exists a DTM running in strict polynomial time such that if and only if such that , which implies that if and only if , . In both cases, . Then, a simple dIP for is the following: (a) the prover , on input , simply computes a witness such that and sends to the verifier ; (b) outputs . It is not hard to see that this dIP satisfies the above definition.

-

. Let . Then, there exists a -round dIP such that

- ;

- ; and

- .

We construct a NP verifier to decide . will simply be the final computation performed by the verifier . Recall that the output of the protocol is defined as . We set the witness . Since are all polynomial in for all , we have that . If , then there is a valid witness such that accepts, so will accept. If , then there is no prover strategy that causes the verifier to accept; in other words, all possible transcripts are rejected by the verifier, so always rejects.

The Class IP: Random Verifiers

The above discussion tells us that dIP is no more powerful than NP. It turns out the reason is a lack of randomness in the protocol. Whereas researchers do not believe that BPP is more powerful than P, the class IP, which we define next, will be much more powerful than NP.1

Definition. The class is the set of all languages that have a -round IP such that: is deterministic and computationally unbounded; is a probabilistic polynomial time (PPT) algorithm/machine (that is, runs in strict polynomial time and is allowed to sample random coins); and the following hold:

- (Completeness) If then ; and

- (Soundness) If , then for all , .

The class is defined as .

Some notes about the above definition.

- The verifier in the above definition is not required to reveal the random coins, and can sample coins as a function if its input and the messages it has seen so far. An IP where the verifier does not reveal its randomness to the prover is called a private coin protocol. If all the verifier messages are uniformly random strings, then it is a public coin protocol. We will see later that private coins are not necessary!

- Does being probabilistic change the class IP? No! being computationally unbounded, for any probabilistic strategy, it can optimally compute the messages of this prover strategy to maximize the success probability of the verifier. So they are equivalent. Moreover, this can be done only using space. Intuitively, this implies that .

- As we will see in the below lemma, we can amplify both the completeness and soundness to be arbitrarily close to , which does not change the class . Moreover, the lemma below can be performed in parallel, so the resulting amplified protocol still has rounds.

- In fact, setting the completeness probability equal to (so-called *perfect completeness) does not change the class . This is a non-trivial fact!

- On the contrary, setting the soundness error equal to collapses to .

Lemma. The class remains the same if we require completeness to hold with at least probability and soundness to hold with at most probability for fixed constant .

Proof Sketch. Given with completeness/soundness error , we can construct a new IP which runs sequentially for some number times. The output of is the majority of the answers obtained from . Setting gives us the desired result via a Chernoff bound.

IP for Graph Non-Isomorphism

To demonstrate the power of the class IP, we will give an IP for the graph non-isomorphism problem, which is in coNP. Note that we do not know if languages in coNP have short certificates, and yet we can give an IP with a polynomial sized proof and polynomial-time verification.

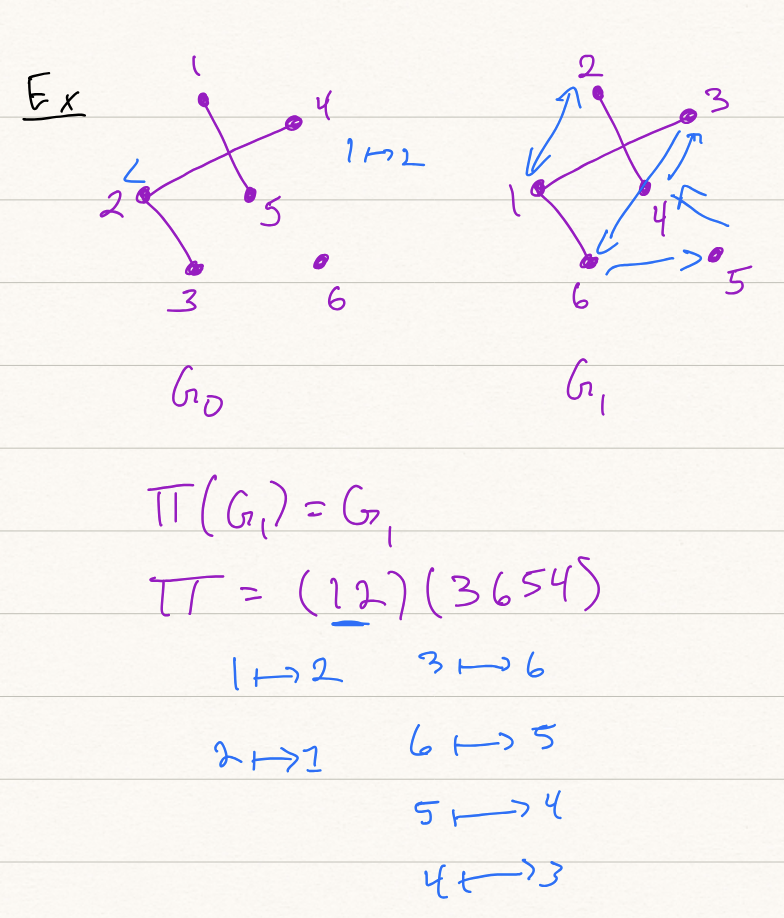

First, let both be undirected simple graphs on vertices. We say that is isomorphic to , which is denoted by , if you can relabel the vertices of and obtain the graph . In other words, there exists a permutation on the set such that (i.e., you relabel the vertices of according to the permutation and obtain the graph ).

The language of graph isomorphism, denoted as , is known to be in NP; it is unknown if is NP-complete (and we have evidence that it is not; we’ll see this in a later lecture). Then, is the graph non-isomorphism problem, and is in coNP.

GNI Interactive Proof

Below, we sketch the interactive proof for . Let be two vertex graphs. Our proof system will operate as follows on input .

- The verifier samples uniformly at random and samples a uniformly random permutation . defines and sends to .

- The prover receives and computes a bit . sends to .

- outputs if and only if .

Analysis

- If , then no exists such that . This means that , being computationally unbounded, can trivially compute from ; i.e., identify which graph is isomorphic to.

- If , then can only guess the correct bit and succeed with probability at most .

GNI with Public Coins?

The above IP for crucially relies on being hidden. It is not hard to see why: if knows , can always respond correctly; the same thing happens if knows . Can we give a IP that uses public coins? To do so, we’ll need to take a more quantitative (but equivalent) approach to .

Let be two vertex graphs. Define a new set as

Notice that it is easy to certify if for any : simply provide a permutation such that or . Now, any graph on vertices can have at most equivalent graphs, where a graph is equivalent to if and . If we pretend that both have exactly equivalent graphs, we know that is the set of all graphs which are equivalent to either or . This leads us to the following observations.

- If , then .

- If , then .

These observations will be a stepping stone to obtaining a public-coin protocol for .

-

Under standard and widely believe complexity theory conjectures. ↩