CS 505 - Computability and Complexity Theory

Welcome to the class! I’m excited to have you. Throughout this website, you’ll find all the relevant information needed for the course.

On this page, I’ll post important announcements, as well as a changelog. If you have any questions, please feel free to reach out to me.

Announcements

- [

May 8, 2025] All grades except for the Final Project write-up have been posted to Blackboard. You also should have received feedback in Blackboard for your project presentations (peer feedback and my own feedback). If you have any questions, contact me as soon as possible. Sample solutions for Homework 5 have been posted. Lecture 20 typed notes posted. - [

April 28, 2025] Final Project write-ups are now required to be submitted via Blackboard. This has been noted on the Final Project page, as well as the PDF included there. Typed notes for Lecture 19 posted. - [

April 26, 2025] Handwritten notes for Lecture 23 and Lecture 24 posted. Additional resources for the PCP theorem posted; see Resources. - [

April 21, 2025] Homework 5 posted. Sample solutions for Homework 3 and Homework 4 posted. Make-up office hours will be held this week: April 23, 2025, at 2:00pm (in-person or via Zoom). - [

April 11, 2025] Lecture 21 and Lecture 22 handwritten notes posted. Recorded lectures for Crypto and Complexity Theory, along with handwritten notes for those lectures, posted. Office Hours next week are cancelled due to travel on my end; I will still be available via email or Piazza. - [

April 7, 2025] Lecture 19 and Lecture 20 handwritten notes posted. Schedule updated. Group orderings for the Final Project presentations posted. Please see the webpage for the schedule (i.e., when your group is presenting), along with how the ordering was decided. - [

March 31, 2025] Homework 4 posted. Grades for Homework 3 posted on Gradescope. Schedule updated; no class the week of April 14, instead there will be recorded lectures. - [

March 30, 2025] Typed notes for Lecture 17 and Lecture 18 posted. - [

March 26, 2025] Handwritten notes for Lecture 17 and Lecture 18 posted. Typed notes for Lecture 16 posted. - [

March 17, 2025] Typed notes for Lecture 15 posted. - [

March 16, 2025] Handwritten notes for Lecture 15 and Lecture 16 posted. Typed notes for Lecture 14 posted. Midterm grades posted to Gradescope. - [

March 11, 2025] Final Project information posted. Midterm sample solutions posted to Piazza. Schedule updated with Final Project information. - [

March 3, 2025] Homework 3 posted. Homework 2 sample solutions posted. - [

March 1, 2025] Typed notes for Lecture 13 posted. - [

February 28, 2025] Lecture 11 and Lecture 12 typed notes posted. Handwritten notes for Lecture 13 and Lecture 14 posted. - [

February 23, 2025] Lecture 9 and Lecture 10 typed notes posted. Handwritten notes for Lecture 11 and Lecture 12 posted. - [

February 18, 2025] Schedule updated. - [

February 17, 2025] Lecture 9 and Lecture 10 handwritten notes posted. Homework 1 grades released on Gradescope. Sample solutions for Homework 1 posted. - [

February 13, 2025] Homework 2 posted. - [

February 10, 2025] Lecture 7 and Lecture 8 handwritten notes posted. - [

February 04, 2025] Lecture 5 and Lecture 6 posted. - [

February 03, 2025] Handwritten notes for Lectures 2-6 posted (there are no notes for Lecture 1 since it was written on the board). Lecture 5 and Lecture 6 typed notes will be posted tonight or tomorrow. Zoom link added to office hours (see Important Info below and the Syllabus). - [

January 31, 2025] Homework 1 updated to reflect schedule changes. Problem 5 has been changed. If you do not see this change, you may need to force refresh the course website in your browser, or open it in an incognito window. Schedule updated. - [

January 27, 2025] Lecture 3 and Lecture 4 posted. - [

January 21, 2025] Homework 1 posted. Homework collaboration policy posted. - [

January 20, 2025] In-class lecture on January 21, 2025, is cancelled due to the weather. Class will be held on Zoom. Please check your email for the Zoom link. - [

January 20, 2025] Since today is a holiday and the weather is very cold, in-person office hours are optional. A Zoom link will be sent for office hours today (check your email). - [

January 19, 2025] Lecture 1 and Lecture 2 have been posted. Office hours have been updated (see above or the syllabus).

Important Info

Instructor: Alexander R. Block

Email: arblock [at] uic [dot] edu

Drop-in Office Hours

- Time: Mondays, 2–3pm (or by appointment)

- Location: SEO 1216 or Zoom

- Zoom link (UIC login required): https://uic.zoom.us/j/81305503904?pwd=w4N9MLSrL4M7sny3zQmYyWT6MQgkiG.1

Course Modality and Schedule: In-person only, BSB 289, 2:00 pm - 3:15 pm, Tuesday & Thursday.

Important Links

Changelog

- [

January 20, 2025] Announcements moved to the top of this page. Links to lecture notes added to the schedule and resources. - [

January 19, 2025] Added important info to this page. Announcement on this day posted. - [

January 13, 2025] Syllabus updated. - [

January 06, 2025] Website available.

Syllabus

Instructor and Course Details

Instructor: Alexander R. Block

Email: arblock [at] uic [dot] edu

Drop-in Office Hours

- Time: Mondays, 2–3pm (or by appointment)

- Location: SEO 1216 or Zoom

- Zoom link (UIC login required): https://uic.zoom.us/j/81305503904?pwd=w4N9MLSrL4M7sny3zQmYyWT6MQgkiG.1

Course Modality and Schedule: In-person only, BSB 289, 2:00 pm - 3:15 pm, Tuesday & Thursday.

Blackboard: https://uic.blackboard.com/ultra/courses/_279721_1/cl/outline

Gradescope: https://www.gradescope.com/courses/942742

Piazza: https://piazza.com/uic/spring2025/cs505

Course Announcements

Course information will primarily be conveyed using this website (see here). Course discussion will happen on Piazza. All course assignments and grades will be collected and returned through Gradescope. I will also send email notifications to the class with announcements.

You are responsible for checking this website and emails for any and all updates and information regarding the course, including homework assignments and schedule changes. You are also responsible for keeping up to date on Piazza for any corrections and/or clarifications regarding assignments, or other important information.

Blackboard will be used sparingly in this course, primarily for Homework, Midterm, Final Project, and Final Grades. For all technical questions about Blackboard, email the Learning Technology Solutions team at LTS@uic.edu.

Communication Expectations

Students are responsible for all information instructors send to your UIC email. Faculty messages should be regularly monitored and read in a timely fashion.

Please use Piazza private messages shared with the instructors (not just the professor or TA by name) if you wish to communicate with us directly. Please only use email for something that explicitly should be kept private only to that person.

Please email me if you face an unexpected situation that may impede your attendance, participation in class and exam sessions, or timely completion of assignments.

Course Information

CS 505 is a graduate-level introductory course to Computability and Complexity Theory. You will be expected to read, understand, and write formal (i.e., mathematic) proofs.

Prerequisites: For UIC students, CS 305 is listed as a prerequisite. However, most (if not all) topics covered will be self-contained in this course. As stated above (but in another way), you will need mathematical maturity to succeed in this course. That is, you should be comfortable answering questions of the form “prove or disprove the following statements.” If you are able to do this, then this course is for you; if you struggle with these types of problem, then this course may not be for you.

Brief list of topics to be covered (subject to change)

- Turing machines and their equivalent computational models

- Languages and Decidability

- The class

- The class , and -Completeness

- Randomized Computations

- Space Complexity

- Interactive proofs;

- (Time-dependent) Cryptography and Complexity Theory

Required and Recommended Course Material: No textbook is required for this course. Lectures will have all relevant information.

I will be closely following the book Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach by Aurora and Barak. I will additionally use material from Introduction to the Theory of Computation by Michael Sipser, Mathematics and Computation by Avi Widgerson, and Proofs, Arguments, and Zero-Knowledge by Justin Thaler.

I will give suggested additional readings for each lecture in relevant material freely available online.

Course Copyright: Please protect the copyright integrity of all course materials and content. Please do not upload course materials not created by you onto third-party websites or share content with anyone not enrolled in our course.

The purpose of this syllabus is to give students guidance on what may be covered during the semester. I intend to follow the syllabus as closely as possible; however, I also reserve the right to modify, supplements, and/or make changes to the course as needs arise. All such changes will be communicated in advance through in-class annoucnements and in writing via this website and email.

Course Policies and Classroom Expectations

Grading Policies & Point Breakdown

Grades will be curved based on an aggregate course score and are not defined ahead of time. The score cut-offs for A, B, C, etc., will be set after the end of the course.

The course will have the following grade breakdown:

| Task | % of total grade |

|---|---|

| Homework | 40% |

| Midterm Exam | 25% |

| Final Project | 35% |

Final Grade Assignments

My goal is to ensure that the assessment of your learning in this course is comprehensive, fair, and equitable. Your grade in the class will be based on the number of points you earn out of the total number of points possible, and is not based on your rank relative to other students. There are no set limits to the number of grades given (e.g., everyone can get an A if everyone does well). If the class average is at least 75%, then assigned letter grades will be based on a straight scale with the following thresholds:

| Grade | Threshold |

|---|---|

| A | 90% |

| B | 80–89.9% |

| C | 70–79.9% |

| D | 60–69.9% |

| F | 60% |

If the class mean is less than 75%, then this scale will be adjusted to compensate.

Under no circumstances will grades be adjusted down (except in cases of course policy violation). You can use this straight grading scale as an indicator of your minimum grade in the course at any time during the course. You should keep track of your own points so that at any time during the semester you may calculate your minimum grade based on the total number of points possible at that particular time. If and when, for any reason, you have concerns about your grade in the course, please email me to schedule a time for you to speak with me so that we can discuss study techniques or alternative strategies to help you.

Regrade Policy

You are allowed to request one single regrade per homework assignment/non-final exam. Moreover, with every regrade request, you must submit the following information:

- Which problems you are requesting a regrade for; and

- The exact reason you are requesting a regrade.

I will be strict with this policy to ensure there are no frivolous regrade requests; i.e., do not request a regrade to try and argue for more points. You must have a specific and articulate reason for why you believe something was graded incorrectly. Finally, note that any regrade request can result in a score reduction if additional errors are discovered.

Homework Late Policy

All homework assignments are due by the beginning of class (2:00pm Central Time) on the day they are due. You may submit homework late, with a 25% point reduction per day of being late. On the fourth day of being late, you will receive zero points on the assignment, but it will still be graded in order to give you feedback.

In-class Participation

All course material will be primarily given through in-class lectures. However, as this is a graduate course, I will not require you to attend lecture, but it will be highly encouraged. You are responsible for submitting all assignments, taking the midterm exam, and completing the final project.

Note that though you are not required to attend lecture, I will not answer questions in office hours of the form “can you explain X?” when X was explained in class. By not attending lecture, you do not then get to ask me to teach you the lecture material in office hours.

Evaluation

Homework

There will be 4-5 homework assignments in this course, depending on our progress through the semester. Each homework assignment will be weighted equally when calculating your final grade. See here for more information about completing homework assignments.

Note that your lowest homework score will be automatically dropped from your final grade.

Midterm Exam

There will be an in-class midterm exam, covering topics from (roughly) the first half of the course. The tentative date for the midterm exam is Thursday, March 6, 2025, with an in-class review planned for the previous lecture on Tuesday, March 4, 2025. Please plan to attend class on this day for the midterm exam. I will notify all students once the midterm exam date is finalized, and will do so as soon as possible.

Final Project

In place of a final exam, there will instead be a final project. It will consist of both a written portion and an in-class presentation. Your grade will be assigned based on the written portion, the in-class presentation, and peer-evaluations as well. I will give more details about the final project as we get closer to the midpoint of the semester.

Academic Integrity

Consulting with your classmates on assignments is encouraged, except where noted. However, turn-ins are individual, and copying proofs from your classmates is considered plagiarism. You should never look at someone else’s writing, or show someone else your writing. Either of these actions are considered academic dishonesty (cheating) and will be prosecuted as such.

To avoid suspicion of plagiarism, you must specify your sources together with all turned-in materials. List classmates you discussed your homework with and webpages/resources from which you got inspiration and help. Plagiarism and cheating, as in copying the work of others, paying others to do your work, etc., is obviously prohibited, and will be reported (this includes asking questions and copying answers from forums such as Stack Overflow and Reddit).

I report all suspected academic integrity violations to the dean of students. If it is your first time, the dean of students may provide the option to informally resolve the case – this means the student agrees that my description of what happened is accurate, and the only repercussions on an institutional level are that it is noted that this happened in your internal, UIC files (i.e., the dean of students can see that this happened, but no professors or other people can, and it is not in your transcript). If this is not your first academic integrity violation in any of your classes, a formal hearing is held and the dean of students decides on the institutional consequences. After multiple instances of academic integrity violations, students may be suspended or expelled. For all cases, the student has the option to go through a formal hearing if they believe that they did not actually violate the academic integrity policy. If the dean of students agrees that they did not, then I revert their grade back to the original grade, and the matter is resolved.

If you are found responsible for violating the academic integrity policy, the penalty can range from receiving a zero on the assignment in question, receiving a grade deduction, or receiving an F in the class, depending on the severity of the violation.

As a student and member of the UIC community, you are expected to adhere to the Community Standards of academic integrity, accountability, and respect. Please review the UIC Student Disciplinary Policy for additional information.

GenAI

Since this course will be rigorous in formal (i.e., mathematical proofs), the use of GenAI is NOT allowed. As we will see, there are computational tasks that are impossible in any computational model, thus it is highly likely (and, indeed, expectd) that GenAI would answer any such questions incorrectly.

Failure to adhere to this policy will result in the following consequences:

- First use: You will lose 50% of the points available on the assignment.

- Second use: You will fail the assignment.

- Third use: You will fail the course.

Accommodations

Disability Accommodation Procedures

UIC is committed to full inclusion and participation of people with disabilities in all aspects of university life. If you face or anticipate disability-related barriers while at UIC, please connect with the Disability Resource Center (DRC) at drc.uic.edu, via email at drc@uic.edu, or call (312) 413-2183 to create a plan for reasonable accommodations. To receive accommodations, you will need to disclose the disability to the DRC, complete an interactive registration process with the DRC, and provide me with a Letter of Accommodation (LOA). Upon receipt of an LOA, I will gladly work with you and the DRC to implement approved accommodations.

Religious Accommodations

Following campus policy, if you wish to observe religious holidays, you must notify me by the tenth day of the semester. If the religious holiday is observed on or before the tenth day of the semester, you must notify me at least five days before you will be absent. Please submit this form by email with the subject heading: “[CS 505] YOUR NAME: Requesting Religious Accommodation.”

Classroom Environment

Inclusive Community

UIC values diversity and inclusion. Regardless of age, disability, ethnicity, race, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, geographic background, religion, political ideology, language, or culture, we expect all members of this class to contribute to a respectful, welcoming, and inclusive environment for every other member of our class. If aspects of this course result in barriers to your inclusion, engagement, accurate assessment, or achievement, please notify me as soon as possible.

Name and Pronoun Use

If your name does not match the name on my class roster, please let me know as soon as possible. My pronouns are [she/her; he/him; they/them]. I welcome your pronouns if you would like to share them with me. For more information about pronouns, see this page: https://www.mypronouns.org/what-and-why.

Community Agreement/Classroom Conduct Policy

- Be present by removing yourself from distractions, whether they be phone notifications, entire devices, conversations, or anything else.

- Be respectful of the learning space and community. For example, no side conversations or unnecessary disruptions.

- Use preferred names and gender pronouns.

- Assume goodwill in all interactions, even in disagreement.

- Facilitate dialogue and value the free and safe exchange of ideas.

- Try not to make assumptions, have an open mind, seek to understand, and not judge.

- Approach discussion, challenges, and different perspectives as an opportunity to “think out loud,” learn something new, and understand the concepts or experiences that guide other people’s thinking.

- Debate the concepts, not the person.

- Be gracious and open to change when your ideas, arguments, or positions do not work or are proven wrong.

- Be willing to work together and share helpful study strategies.

- Be mindful of one another’s privacy, and do not invite outsiders into our classroom.

Furthermore, our class (in person and online) will follow the CS Code of Conduct. If you are not adhering to our course norms, a case of behavior misconduct will be submitted to the Dean of Students and to the Director of Undergraduate Studies in the department of Computer Science. If you are not adhering to our course norms, you will not get full credit for your work in this class. For extreme cases of violating the course norms, credit for the course will not be given.

Student Parents

I know well how exhausting balancing school, childcare, and work can be. I would like to help support you and accommodate your family’s needs, so please don’t keep me in the dark. I hope you will feel safe disclosing your student-parent status to me so that I can help you anticipate and solve problems in a way that makes you feel supported. Unforeseen disruptions in childcare often put parents in the position of having to choose between missing classes to stay home with a child or leaving them with a less desirable backup arrangement. While this is not meant to be a long-term childcare solution, occasionally bringing a child to class in order to cover gaps in care is perfectly acceptable. If your baby or young child comes to class with you, please plan to sit close to the door so that you can step outside without disrupting learning for other students if your child needs special attention. Non-parents in the class, please reserve seats near the door for your parenting classmates or others who may need to step out briefly.

Academic Success, Wellness, and Safety

We all need the help and the support of our UIC community. Please visit my drop-in hours for course consultation and other academic or research topics. For additional assistance, please contact your assigned college advisor and visit the support services available to all UIC students.

Academic Success

- UIC Tutoring Resources

- College of Engineering tutoring program

- Equity and Inclusion in Engineering Program

- UIC Library and UIC Library Research Guides.

- Offices supporting the UIC Undergraduate Experience and Academic Programs.

- Student Guide for Information Technology

- First-at-LAS Academic Success Program, focusing on LAS first-generation students.

Wellness

-

Counseling Services : You may seek free and confidential services from the Counseling Center at https://counseling.uic.edu/.

-

Access U&I Care Program for assistance with personal hardships.

-

Campus Advocacy Network : Under Title IX, you have the right to an education that is free from any form of gender-based violence or discrimination. To make a report, email TitleIX@uic.edu. For more information or confidential victim services and advocacy, visit UIC’s Campus Advocacy Network at http://can.uic.edu/.

Safety

- UIC Safe App—PLEASE DOWNLOAD FOR YOUR SAFETY!

- UIC Safety Tips and Resources

- Night Ride

- Emergency Communications: By dialing 5-5555 from a campus phone, you can summon the Police or Fire for any on-campus emergency. You may also set up the complete number, (312) 355-5555, on speed dial on your cell phone.

Schedule

This schedule is tentative and subject to change. Any changes will be announced.

| Lecture Number (Date) | Topics | Announcements | Additional Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lecture 1 (Jan 14) |

| ||

| Lecture 2 (Jan 16) |

| Correction from in-class lecture; see Lecture 2. | |

| Lecture 3 (Jan 21) |

| Homework 1 assigned. | |

| Lecture 4 (Jan 23) |

| ||

| Lecture 5 (Jan 28) |

| ||

| Lecture 6 (Jan 30) |

| Problem 5 of Homework 1 will be changed to reflect change in schedule. | |

| Lecture 7 (Feb 4) |

| ||

| Lecture 8 (Feb 6) |

| Homework 1 due. | |

| Lecture 9 (Feb 11) |

| ||

| Lecture 10 (Feb 13) |

| Homework 2 assigned. | |

| Lecture 11 (Feb 18) |

| ||

| Lecture 12 (Feb 20) |

| ||

| Lecture 13 (Feb 25) |

| ||

| Lecture 14 (Feb 27) |

| Homework 2 due. | |

| Midterm Review (Mar 4) | Covers Lectures 1-13 (Up to and Alternation) | Homework 3 assigned. | |

| Midterm Exam (Mar 6) | Covers Lectures 1-13 | ||

| Lecture 15 (Mar 11) |

| Final Project information posted. | |

| Lecture 16 (Mar 13) |

| ||

| Lecture 17 (Mar 18) |

| ||

| Lecture 18 (Mar 20) |

| Homework 3 due. | |

| Mar 22, 11:59pm CDT | Final Project proposals due. | ||

| NO CLASS; SPRING BREAK (Mar 25) | |||

| NO CLASS; SPRING BREAK (Mar 27) | |||

| Lecture 19 (Apr 1) |

| Homework 4 assigned. | |

| Lecture 20 (Apr 3) |

| ||

| Lecture 21 (Apr 8) |

| ||

| Lecture 22 (Apr 10) |

| ||

| NO CLASS; Recorded Lecture (Apr 15) |

| Homework 4 due. | |

| NO CLASS; Recorded Lecture (Apr 17) |

| ||

| Lecture 23 (Apr 22) |

| Homework 5 assigned. | |

| Lecture 24 (Apr 24) |

| ||

| Final Project Presentations (Apr 29) | |||

| Final Project Presentations (May 1) | |||

| May 6, 2:00pm CDT | Homework 5 due. | ||

| May 10, 11:59pm CDT | Final Project written reports due. |

Resources

This page will be updated throughout the semester with new resources as I find them. If you have found a particularly useful resource, feel free to let me know and I will gladly add them to the resources below.

Lecture Notes

- Lecture 1

- Lecture 2

- Lecture 3

- Lecture 4

- Lecture 5

- Lecture 6

- Lecture 7

- Lecture 8

- Lecture 9

- Lecture 10

- Lecture 11

- Lecture 12

- Lecture 13

- Lecture 14

- Lecture 15

- Lecture 16

- Lecture 17

- Lecture 18

- Lecture 19

- Lecture 20

- Lecture 21

- Lecture 22

- Lecture 23

- Lecture 24

- Crypto and Complexity Theory

Books

- Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach (Draft) by Sanjeev Arora and Boaz Barak

- Introduction to the Theory of Computation1 by Michael Sipser

- Proofs, Arguments, and Zero-knowledge by Justin Thaler

- Mathematics and Computation by Avi Widgerson

Other Lecture Notes and Videos

- Michael Sipser’s Theory of Computation Course at MIT

PCP Theorem

- Notes from Jon Katz: first lecture and second lecture. All his other notes from this course: website.

- Dana Moshkovitz’s Tale of the PCP Theorem.

- Irit Dinur’s alternative proof of the PCP Theorem: The PCP Theorem by Gap Amplification.

- PCP Theorem Course by Irit Dinur and Dana Moshkovitz: Probabilistically Checkable Proofs.

-

You may be able to find the book online for free. I cannot confirm or deny the availability. Supplemental readings may be given from this book and will be paired with the appropriate video lecture from Michael Sipser’s course below. ↩

Homework

This page will be updated with homework assignments as they become available throughout the semester. All homework assignments will be due before the start of class. That is, by no later than 2:00pm Central US Time.

All homework is required to be typeset in .

Included with each assignment is a .pdf file of the assignment, along with a .zip folder with the source for you to use to complete the assignment.

All homework is required to be submitted through Gradescope.

For submission, you will simply need to upload the .pdf file of your assignment.

You will likely not be able to answer all the questions in a given homework when it is released. My intention is to spread out the material you need to complete each homework over several lectures. This will allow you to either (a) do the homework problems incrementally as we cover the relevant material in class; (b) wait until all lectures are completed then do the homework all at once; or (c) finish the homework as soon as it’s assigned by reading ahead in other resources.

The schedule below is tenative and is subject to change based on how we progress through the semester.

Collaboration between sutends is encouraged. However, all collaborations need to be acknowledged (whether they are in this class, or outside of this class). You MUST list all collaborators for homework assignments. Moreover, collaborating does not mean you can copy-paste work from each other. Each submission needs to be in your own words, otherwise it will be considered plagiarism.

You are allowed to look to other resources for help with the homework, but you MUST properly cite these sources.

Please use the \cite command and add your citations in the proper format to the included local.bib in your homework assignments.

Finally, please acknowledge any other discussions that helped you complete this assignment. This can include “office hours,” “Piazza,” or other discussions where direct collaboration did not happen.

Failing to adhere to the collaboration policy outlined above will result in various penalties.

First violation: You will lose 50% of the points available on the assignment.

Two or more violations: You will fail the assignment.

Homework 1

Date Assigned: January 21, 2025.

Due Date: February 6, 2025, no later than 2:00pm Central Time.

Updated: January 31, 2025 (see Announcements).

PDF file: homework-1.pdf (SHA256: bfcb1bb09bcb433c2e22b462bd1a9ea62d227767936db3099261afcfa3124a37)

Source files: homework-1.zip (SHA256: 73fedc2f3141d71314fe451f2732bf6a7c1dcbf14df8d14c0de05d24289d69d4)

Sample solutions: homework-1-solutions.pdf

Homework 2

Date Assigned: February 13, 2025.

Due Date: February 27, 2025, no later than 2:00pm Central Time.

PDF file: homework-2.pdf (SHA256: 38ade5b4a4b5abd0070c33953861e201253efbcd5fc32dc904abc1314a4a1e54)

Source files: homework-2.zip (SHA256: 5e55f481dcc61aa5489875fc1e00084b1b02081c98fb6657d74551c543276b8b)

Sample solutions: homework-2-solutions.pdf

Homework 3

Date Assigned: March 4, 2025.

Due Date: March 20, 2025, no later than 2:00pm Central Time.

PDF file: homework-3.pdf (SHA256: 276a2dea7f34c264b355968bc90c7052889816082c7c1c179566c9b25537d980)

Source files: homework-3.zip (SHA256: 6e9e6b22715ba055dd1a884bdc18078851629992db7a628051c5ccc41d263635)

Sample solutions: homework-3-solutions.pdf

Homework 4

Date Assigned: April 1, 2025

Due Date: April 15, 2025, no later than 2:00pm Central Time.

PDF file: homework-4.pdf (SHA256: c1d1204ea77d579a379c6d25efb81fffcfc769317e754046a9b2e49ab69a1f31)

Source files: homework-4.zip (SHA256: 75ad92909df75544821d88a3a529bf07d6c7748c31b0114c9ba2df1104bcf7ed)

Sample solutions: homework-4-solutions.pdf

Homework 5

Date Assigned: April 22, 2025

Due Date: May 6, 2025, no later than 2:00pm Central Time.

PDF file: homework-5.pdf (SHA256: 01a81895717cab5d20fe83c7506f7293a02586af0fa53084c2865c5c6d1cf40c)

Source files: homework-5.zip (SHA 256: 19aeb9c23d39e0827c41b72213d6f64851bfa3ee5644e3477a50800565e00b9e)

Sample solutions: homework-5-solutions.pdf

Final Project

Final Project Group Presentation Schedule

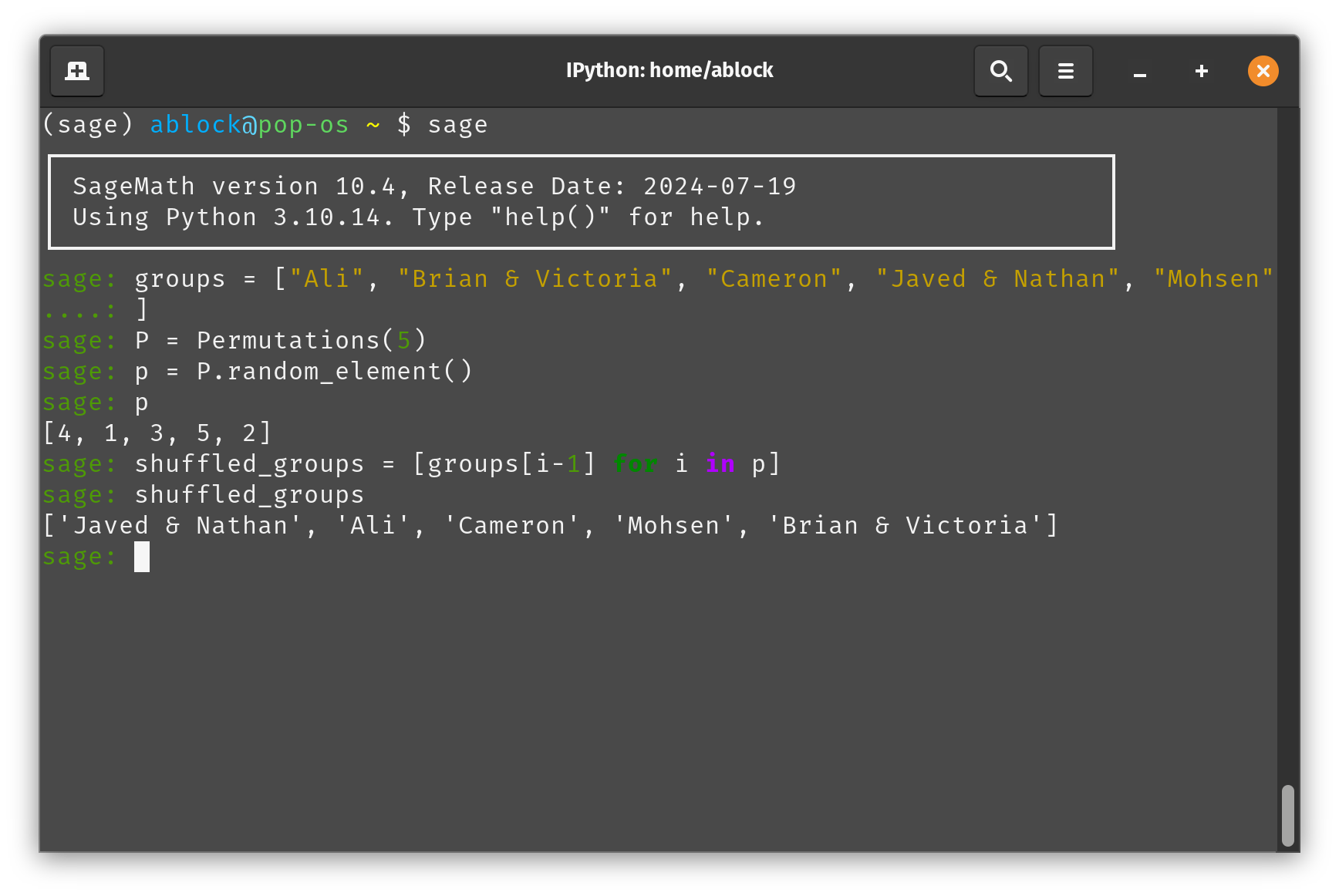

I have randomly generated the Final Project Presentation schedule, as outlined below. The methodology is as follows.

- List all groups in alphabetical order by first name, with each group being sorted alphabetically by first name internally.

- Randomly generate a permutation to shuffle this alphabetical ordering.

- Output the shuffled ordering. First 3 groups present on Tuesday, April 29, 2025; last 2 groups present on Thursday, May 1, 2025.

Groups

- Ali

- Brian & Victoria

- Cameron

- Javed & Nathan

- Mohsen

Random permutation sampled: [4, 1, 3, 5, 2].

Final Ordering

Tuesday, April 29, 2025

- Javed & Nathan

- Ali

- Cameron

Thursday, May 1, 2025

- Mohsen

- Brian & Victoria

Sagemath Code used to generate this result.

groups = ["Ali", "Brian & Victoria", "Cameron", "Javed & Nathan", "Mohsen"]

P = Permutations(5) # set of all permutations on [1,2,3,4,5]

p = P.random_element() # samples a random permutation of the list [1,2,3,4,5]

p # prints the sampled permutatation

shuffled_groups = [groups[i-1] for i in p]

shuffled_groups # prints the new ordering for 'groups'

Code screenshot below.

Project Description

The project you choose can be related to your research area, or completely unrelated. You may work in teams of up to 3 people. However, whatever your project is and however many people you have on your team, the project will consist of two major components—an In-Class Presentation, and a Written Report—as well as two minor components—Project Proposals and Peer Evaluations. There are no rigid page limits for the report; anything between 4–20 pages can work. For the In-Class presentation, you are expected to give a 15–18 minute presentation using the presentation materials of your choice (e.g., PowerPoint, Keynote, , Google Slides, a Board Talk, etc.).

The project can be a survey of a problem or topic of your choice, or a novel analysis of a problem that you like. In the first case, if you read some papers and summarize them in a survey, give the reader the required background (which may be covered only briefly in some conference papers) together with the main results and their proofs and open questions. For the second scenario, if you try to solve a problem that you are interested in, explain the connections with previous work; in case you don’t arrive to a solution by the end of the term, show what approaches you tried and what didn’t work.

The goal of the project is to understand a problem as much as possible, and to give you experience with complexity theory research. Give the reader the background and necessary explanations to make the problem very clear, understand the contribution of the paper, and the approaches used. You do not have to summarize every theorem in the paper (in either write-up or presentation). Pick instead one or a couple of results in the paper(s) you are reading and focus on those, while trying to answer questions such as: What is the idea of the proof? What techniques are the authors using? Where are the difficulties? What are the remaining open questions?

Recent proceedings of good conferences that publish theoretical work are a possible starting point. Some examples are STOC/FOCS/ITCS/SODA/APPROX-RANDOM, CRYPTO/TCC, EC (Economics and Computation), COLT, PODC.

Project Timeline

-

Saturday, March 22, 2025, by 11:59pm CDT. Submit your project proposals to me. This includes at least one paragraph about your project, along with at least one (or, ideally, a few) papers you plan to read for the project. The easiest way to do this is to email me, cc your team members, and include the relevant information in the email.

-

Tuesday, April 29, 2025, and Thursday, May 1, 2025. The last week/last two classes, we will hold the in-class presentations. Attendance will be required except for special cases. Part of this project is to give you experience presenting material you may not be very familiar with or an expert in to an audience who will be even less familiar with your topic. Also, you will be giving peer evaluations to your fellow students as well, and everyone will be required to submit these peer evaluations.

-

Saturday, May 10, 2025, by 11:59pm CDT. Your written reports are due the day after finals. I want to give you as much time as possible for the written reports, but I will still need to read and grade them before grades are due. Early submissions (e.g., before finals) are also fine. You will submit your written reports via

GradescopeBlackboard.

Grade Brakedown

- (5%) Project Proposals

- (10%) Peer Evaluations

- (40%) In-Class Presentation

- (45%) Written Report

Lecture 1

Review

Math Notation

Here are some common math notations we will be using throughout the semester. Any other notation introduced in lecture outside what is presented here will be explained. Please do not be afraid to ask questions about notation in class.

We let denote the set of all integers and let denote the set of natural numbers (i.e., non-negative integers). The set denotes the set of all positive integers. We let denote the set of all real numbers, with and defined to be the ceiling and floor of , respectively (i.e., round up or round down to the nearest integer). All logarithms are base 2 unless otherwise stated; i.e., . When need, we let denote the natural logarithm.

Sets and Strings

Let be a finite set. We say that is a string with alphabet if it is a finite ordered tuple with elements in . That is, if has length , then (i.e., it is a vector). We let denote the set of all finite length strings with alphabet (i.e., the set of all finite length vectors with elements in ). Given two strings and , we let denote their concatenation; sometimes, we also use or to denote their concatenation as well. Finally, given a string/vector , we let denote the length of the string (i.e., number of elements in ). When needed, we let denote the bit-length of ; that is, the number of bits needed to represent . If , then .

Languages

Much of this course will be concerned with the idea of a language. A language is simply a set . A language can be finite or infinite. While the above definition doesn’t really mean much, we’ll see later in the course how we define languages in more meaningful ways.

Function Notation

Let and be arbitrary sets (not necessarily finite). Then we let denote a function from to .

Big-Oh Notation

Let be two functions. We way that is big-oh of if there exists and constant such that for all , we have . We denote this as or . Similarly, we say that is big-omega of if ; we denote this as . We say that is theta of if and .

We say that is little-oh of if for all constants , there exists such that for all , it holds that . We denote this as . Similarly, is litte-omeaga of if ; equivalently, for all constants , there exists such that for all , it holds that . We denote this as .

Turning Machines

The goal of complexity theory is to quantify and measure computational efficiency. How can we do this? It is first necessary to establish a concrete model of computation. But this seems impossible—surely, there are infinite computational models one can cook up to get the job done, right?

Fortunately, we can focus on a single model of computation: the Turning Machine. For (nearly)1 every physically realizable system we have been able to come up with, the Turing machine can efficiently simulate this other model. This gives us a single model with which we can try to understand and quantify computational efficiency.

Turing Machines, Informally

Turing machines, introduced by Alan Turing in 1948, are an attepmt to formalize the idea of computation as people have understood it for centuries. Intuitively, when someone asks you to compute the answer to a problem, we as people seem to follow a basic formula for realizing this:

- Get the problem, along with the inputs to the problem.

- Get a piece of scratch paper to work on.

- Apply a set of rules to the inputs and make decisions according to those rules.

- Arrive at an answer to the problem, state the answer, and stop working.

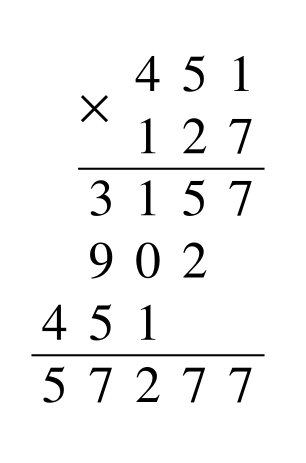

As a concrete example, consider the problem of multiplying two integers. Take and and suppose we want to compute their product . There is a simple (so-called “grade-school”) algorithm for computing , which we show in the figure below.

Turing machines attempt to formalize the above intuitive process, but in a very restricted capacity (i.e., Turing machines are incredibly simple and, in a word, stupid).

Turing Machines, Formally

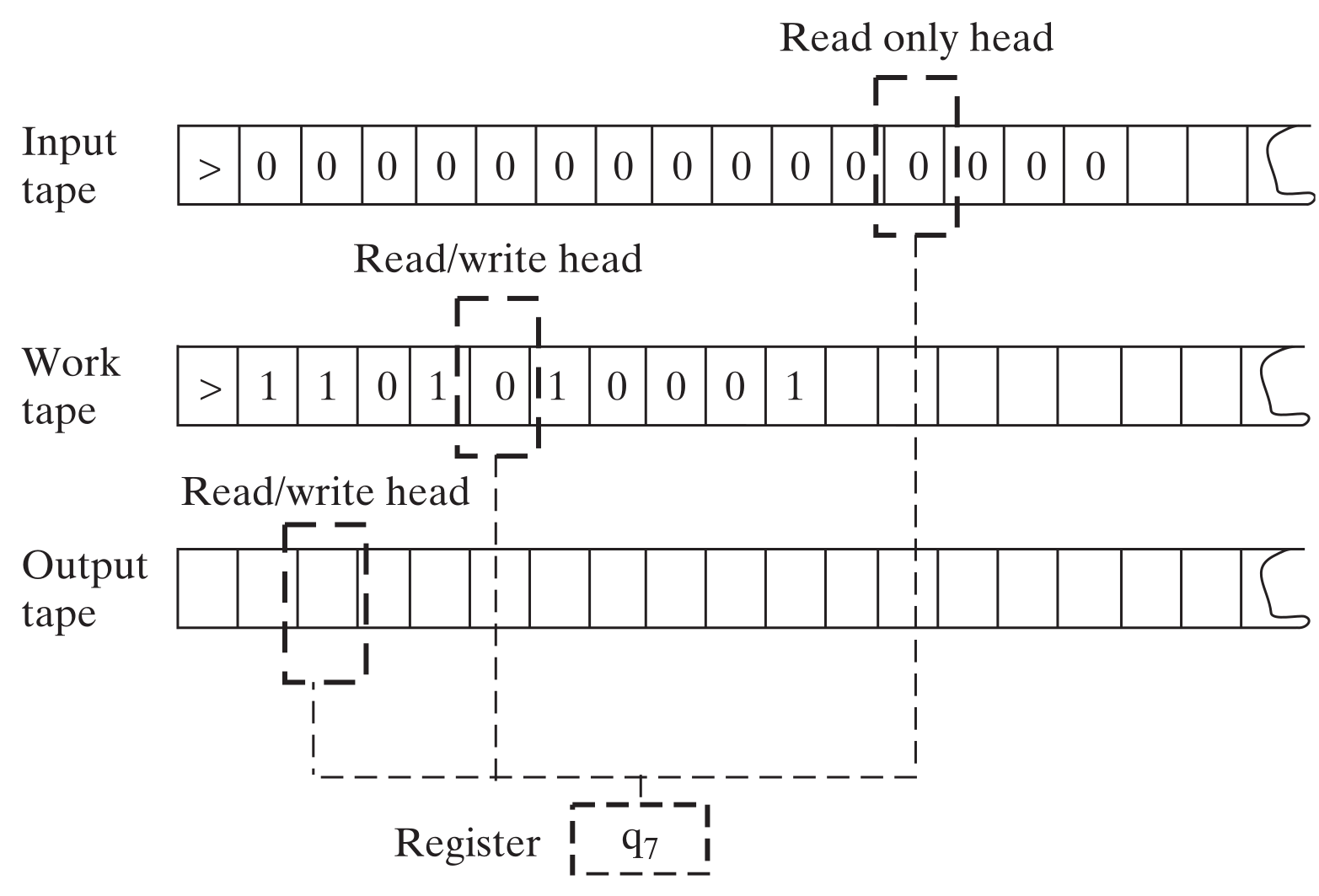

A -tape Turing machine, which we denote by , is a machine with tapes that are infinitely long in one direction (i.e., they are represented by the set ). The machine has a single read-only input tape, a single read-write output tape, and read-write work tapes. also contains a register which tracks the machine’s state. Each head can be moved independently. More formally, a -tape Turing machine is described by a tuple with the following properties:

- is a finite set, which we call the input alphabet;

- is called the tape alphabet, and it contains along with two special symbols that are not in . is the start symbol and is the blank symbol.

- is a finite set of states which can be held in the register. always contains two special states: (the start state) and (the halt state).

- A transition function describing the rules follows during a computation.

We say that a tuple is a configuration of the Turing machine . In this light, the transition function maps configurations of the Turing machine to new configurations as follows:

- represents the current state of the machine stored in its register;

- represents the current symbol under tape ’s head, for ;

- reads the current state and the contents of the tape heads.

It then outputs a new configuration , where

- is the new state stored in the register;

- is a new symbol that is written under the th tape head for (i.e., it excludes the input tape); and

- specifies moving tape head one space Left, one space Right, or telling the tape head to Stay.2

- If the Turing machine is ever in the state , it stops executing the transition function and halts.

Additionally, all Turing machines satisfy the following.

- All tapes are initially set with in every location.

- The first index of every tape is then initialized to . All tape heads begin here.

- On input , all Turing machines will:

- Move the input head , then write to the input tape.

- Move the input head until it reaches .

- Set the initial state in the register to . The Turing machine is now ready to begin its computation.

We call this the initial configuration of the Turing machine.

A graphical example of a -tape Turing machine is presented below.

Turing machine example: Palindromes

Let’s see an example of a Turing machine in action. We will be using Turing machines to compute functions. Let be a function such that if and only if is a palindrome. That is, ; equivalently, if , then for all . Let’s design a Turing machine for computing .

High-level TM Specification. Let be a -tape Turing machine (1 input, 1 output, 1 work tape). On input for any , will do the following.

-

Copy the input to the work tape.

-

Move the input head to the start of the input tape (with under the head), leave the work head at the last position (with under the head).

-

Move the input head one position right (with under the head) and move the work head one position left (with under the head).

-

Read the symbols under the input head and the work head.

(a) If the symbol under the input head is and the symbol under the work head is , then write to the output tape and halt.

(b) Else if the symbols under the input head and work head are not equal, write to the output tape and halt.

(c) Else (i.e., the symbols are equal) move the input head one step right and move the work head one step left.

Formal TM Specification of above. We now formalize thie above process. To do so, we specify (1) the input alphabet; (2) the set of states for ; and (3) the transition function for .

- The input alphabet is simply . This tells us our tape alphabet is .

- The set of states will be .

- The transition function is defined as follows.

Let be a configuration given as input to .

- If , move both the input head and work head right and change the state to .

- If , then read the symbol under the input head (i.e., read ).

- If , write to the current position of the work tape. Then move both the input head and work head one step right. Keep the state as . In this case, the output of the transition function is .

- If , then move the input head left and change the state to . In this case, the output of the transition function is .

- If , read the symbol under the input head (i.e., ).

- If , then move the input head left and keep the state as . In this case, the output of the transition function is .

- If , then move the input head right, move the work head left, and change the state to . In this case, the output of the transition function is .

- If , read what’s under the input and work heads (i.e., and ).

- If and , then write on the output tape and change the state to . In this case, the transition function outputs .

- Else if , then write on the output tape and change the state to . In this case, the transition function outputs .

- Else (i.e., ), then move the input head right and the work head left, keeping the state as . In this case, the transition function outputs .

Turing Machine Equivalences

At first, the Turing machine model seems like a very restrictive model that cannot compute many things, especially real-life computers. However, as we will see, this restrictive computational model is (roughly) equivalent to nearly every other computational model people have thought of over the years. This includes:

- Random access machines;

- Turing machines with write-only output tapes;

- -calculus;

- Single-tape Turing machines;

- Turing machines with bidirectional infinite tapes;

- Pointer and Counter machines;

- Turing machines with only binary input alphabets;

- Oblivious Turing machines.

In the next lecture or two, we will quantify what we mean by Turing machines being equivalent to the above notions.

-

Quantum computers are the one (almost) physically realizable computational model that we have which does not seem to admit efficient simulation on Turing machines. ↩

-

If the Turing machine specifies that a tape head to move left, but it’s at the start of the tape, the head simply stays in the same place. ↩

Lecture 2

In-class notes: CS 505 Spring 2025 Lecture 2

Measuring Runtime of Turing Machines

With the definition of Turing machines established, we can turn towards quantifying the run-time of Turing machines. Informally, the run-time of a Turing machine computing some function is the maximum amount of time needed to compute on all inputs (of a fixed length), where our measure of time corresponds to how many executions of the transition function needs to utilize to compute . First, we need to actually define what it means for a Turing machine to compute a function .

Definition (Turing Machine Computation). Let be a function and let be a Turing machine. We say that computes if for all , when is initialized with input it halts with on the output take. We denote this as .

Now we can define the run-time of a Turing machine computing a function .

Definition (Turing Machine Run-time). Let be a function and let be a Turing machine which computes . Furthermore, let be a function. We say that computes in time if in at most steps for all (i.e., steps). Here, a step of the Turing machine is a single execution of its transition function .

In essence, executing one step of the transition function of a Turing machine is the atomic Turing machine operation.

Time Constructible Functions

An important concept is the idea of time constructible functions, which we will use to quantify and show equivalences among different Turing machine models. It will also be used in later topics (e.g., time hierarchy theorems).

Definition (Time Constructible Function). Let be a function. Then we say that is time construictible if and only if (1) ; and (2) there exists a Turing machine such that for all , we have in time . Here, denotes the binary representation of .

Examples of time constructible functions include Notably, , or any , are not time constructible.

The above examples of non-time constructible functions highlight a key idea behind time constructibility: a Turing machine (usually) needs to read its entire input in order to compute a function. The stipulation allows for a Turing machine to at least read the entire input before computing . If this restriction is removed, then is still time constructible (you simply ignore all inputs and write the constant to the output tape), but remain non-time constructible since the Turing machine is expected to compute in less time than it takes to read !

Turing Machine Equivalences

A function being time constructible turns out to be a key factor in how we define equivalences among Turing machines (and other models as well).1 Informally, we say that a computational model is equivalent to a computational model if any for any computation capable of being performed in can be performed in (with at most polynomial time overhead). In the context of Turing machines, we say that a computational model is equivalent to the Turing machine model if any problem solvable in time in model can be solved by a Turing machine running in time for constant . Intuitively, if is a program in computational model running in time , then a Turing machine will simulate model in order to run program (e.g., similar to modern interpreted programming languages like Python). If runs in time , and is not time constructible, then this simulation will not meet our requirements; i.e., it will not be an efficient simulation.

As mentioned in Lecture 1, the -tape Turing machine model we have been working with is equivalent to many other Turing machine (and non-Turing machine) models. We state these relations formally below.

First, recall that it is sufficient to consider a Turing machine which only uses a binary alphabet.

Lemma 2.1. For every and time constructible , if is computable in time by a Turing machine with tape alphabet , then it is computable in time by a Turing machine with tape alphabet .

Proof Sketch. The main idea is to encode the (non-start and non-blank) symbols of using bits. This requires roughly bits to uniquely encode in binary. Then the new Turing machine simply encodes each symbol from on its tapes in binary. To simulate a single step of , the machine must read bits from each tape, translate the symbol read into its current state, then execute ’s transition function.

Next, it turns out that any -tape Turing machine can be readily simulated by a single-tape Turing machine (which many of you may have seen before).

Lemma 2.2. For every and time constructible , if is computable in time by a -tape Turing machine, then it is computable in time by a single-tape Turing machine.

Proof Idea. The proof idea is to stagger the tapes onto the single-tape machine. Notably, since each of the tapes is infinite, if you try to write them side-by-side on a single-tape machine, you would inevitably run into a situation where you reach the end of an allocation for a work tape, so you’d have to shift the entire contents of the remaining tapes right one space. This would blow-up the time to simulate. So instead, you stagger the tapes. Consider tape . Then positions of tape would be written to positions on the single-tape machine.

It also turns out that having tapes which are infinite in both directions does not buy you much in terms of computational efficiency.

Lemma 2.3. For every and time constructible , if is computable in time by a -bidirectional tape Turing machine (i.e., every tape is infinite in both directions), then is computable in time by a standard -tape Turing machine (i.e., tapes that are infinite in one direction).

Proof Idea. You can approach this two different ways.

-

Cut each bidirectional tape in half, then stagger this tape onto a single tape (similar to Lemma 2.2 above).

-

If the bidirectional Turing machine has tape alphabet , let the standard Turing machine have tape alphabet . Then you can encode the bidirectional tape onto the single tape using .

Universal Turing Machines

We’ve discussed how our -tape Turing machine is equivalent to many other Turing machine models. Next, we will see that we can simulate any Turing machine (in any equivalent model). Much like how the modern computer can run any computation you give it, we will see there is a universal Turing machine which can simulate any Turing machine you give it as input.

Turing Machines are (Binary) Strings

We’ve focused our attention on Turing machines which compute some function , and we haven’t given much thought to how we write down the machine . It turns out that we can conveniently describe Turing machines simply as binary strings. We’ll let denote the binary string which represents the Turing machine . Note: there are an infinite number of strings which represent a single Turing machine .

For any , we will let denote the Turing machine specified by the string . In this light, notice that

- We’ve always talked about Turing machines computing some function ;

- Turing machines themselves are such a function; and

- Turing machines can also be inputs to these functions!

So there must be a Turing machine which can take Turing machines as input and compute the function that this Turing machine would have computed! This is the universal Turing machine.

Theorem 2.4 (Hennie & Stearns, 1966). There exists a Turing machine such that for all , . That is, computes the output of when run with input . Moreover, if halts within steps on any input for time constructible , then halts in steps, where the hidden constant only depends on ’s alphabet size, number of states, and number of tapes.

The proof of the above theorem can be found below (see Proof of Theorem 2.4). Here, we’ll give the proof of the above with replaced with .

Proof with time bound . Suppose that . Without loss of generality, we can assume that the Turing machine has tape alphabet and has a single work tape (i.e., it is a -tape Turing machine). If not, then can transform into an equivalent Turing machine, denoted as , with these properties by Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2.2 In this case, if runs in time , then the resulting equivalent Turing machine runs in time (ignoring the factors since is fixed).

The universal machine will be a -tape Turing machine; i.e., one input tape, one output tape, and 3 work tapes. has alphabet . Now will simulate as follows.

- uses its input, output, and first work tape to identically copy the operations performs on these tapes (recall has tapes).

- encodes the state space of on its second work tape.

- encodes the transition function of on its third work tape. The transition function is simply encoded as a table of key-value pairs.

In order to simulate a single step of ’s computation, the machine does the following.

- Read the current symbols under the input tape, output tape, and first work tape. This identically matches what does and takes constant time.

- Read the current state of from the second work tape. Since the tape alphabet is binary, the states of take bits to encode, so reading the current state takes time steps (i.e., move to the end of the current state, go back to the start of the work tape).

- Let be the current state, and let be the symbols read from the input, output, and first work tapes, respectively. Scan the third work tape for the key .

- Once this key is found, read the value from the corresponding table entry. The value is exactly , where for .

- Execute the transition function of .

- Write to the output head and to the head of work tape 1. This takes constant time.

- Write the new state to the second work tape and reset the tape head after. This take time.

- Move tape head direction for . This takes constant time.

- Move the head of the third work tape back to the start.

Now, the time complexity of (3) and (5.4) above are the same. In particular, in the worst case, must scan to the end of the table representing to find the correct state. There are keys in this table, and each key has an entry in . Since and because we can encode with only two more bits, we can conclude that each table entry (i.e., each key-value pair) has length . This means to write down a single entry, we need bits. Moreover, there are a total of entries in the table, so the total time of executing (3) or (5.4) is at most time.

Since is fixed, to simulate a single step of on requires time. So if runs in time , then runs in time . Now by the transformation we performed on to obtain . Thus, simulates in at most time.

Turing Machines and Languages

We’ve spent most of our time discussing Turing machines and how they compute functions. We’ll now shift to mostly talking about Turing machines in the context of deciding languages.

Recall that a language is simply a subset of . Notably, we can define a function as if and only if ; this immediately implies that if and only if . So there is a natural correspondence to computing functions and deciding set membership in a language .

Key to our later dealings with complexity classes will be the idea of Turing decidability. We’ll build up to this idea by first introducing Turing recognizability.

Definition (Turing Recognizable Language). A language is said to be Turing recognizable if there exists a Turing machine such that for all , . In particular, always halts and outputs if .

Recognizability only requires that the Turing machine halt on any valid member of the language. If, however, one hands this Turing machine , its behavior is undefined and not guaranteed! We’d like to strengthen this to make sure our Turing machine always halts, whether or not its input is in the language. This gives us decidability.

Definition (Turing Decidable Language). A language is said to be Turing decidable if there exists a Turing machine such that the following hold for any :

- if and only if ; and

- if and only if .

Notice that the above definition immediately means that halts on all possible inputs. This is because, equivalently stated, if then , where is the complement of , which is defined as (i.e., everything in but not in ).

An equivalent definition of decidability states that both the language and its complement are recognizable.

Lemma 2.5. A language is Turing decidable if and only if both and are Turing recognizable.

Undecidability

Unfortunately, there are many (interesting) languages that are undecidable; that is, there does not exist any Turing machine which decides the language. We’ll begin by showing the existence of at least one undecidable language.

Theorem 2.6. There exists a language that not Turing decidable (i.e., it is undecidable).

Proof. First define a language ; i.e., is the set of all strings such that the Turing machine , when given input its own description , halts and outputs . Now define the complement language . We claim that is undecidable.

We show this via a proof by contradiction. So towards contradiction, assume that is decidable. Then there exist a Turing machine which decides this language. This implies that for any , if and only if and if and only if .

Consider . We have that

Thus, we have a contradiction as . This implies that is undecidable.

Notably, the above proof technique is known as diagonalization. We’ll use it later when we discuss time hierarchy theorems.

I incorrectly stated in class that is was recognizable. However, is, in fact, not recongizable. This is because from the above proof is recognizable. By Lemma 2.5, if was Turing recognizable, then it would be decidable, but clearly it is not!

One may argue that the language is not a very interesting language class, and may not come up in the real world. However, we’ll take one-step up and consider a more interesting language that would be great for us if it were decidable! Unfortunately, it is not decidable.

The Halting Problem

The Halting problem asks the following simple question: given a Turing machine , does it halt on input ? More formally, it is specified by the following language:

Theorem 2.7. is undecidable.

We’ll give the proof of this theorem in Lecture 3.

Proof of Theorem 2.4

This proof is taken directly from Arora & Barak’s book with the following notes:

- Theorem 1.9 in the proof corresponds to Theorem 2.3 in these lecture notes;

- Claim 1.6 in the proof corresponds to Lemma 2.2 in these lecture notes; and

- Claim 1.5 in the proof corresponds to Lemma 2.1 in these lecture notes.

The proof can be found in the following pdf: Proof of Theorem 2.4

-

“Key” here meaing it makes proofs much simpler. ↩

-

Lemma 2.2 tells us that a -tape Turing machine can be simulated by a one-tape Turing machine with quadratic overhead. The same proof can be applied to reduce -tapes to -tapes, with a single input, output, and work tape (i.e., transform the work tapes into a single work tape, keep the input/output tapes the same). ↩

Lecture 3

In-class notes: CS 505 Spring 2025 Lecture 3

Undecidability Wrap-up

We begin by wrapping up our discussion of undecidability.

The Halting Problem

From last time, we’ll finish proving that the halting problem is undecidable. First, recall the definition of the halting problem.

Theorem 2.7. is undecidable.

Proof. We’ll prove this via a reduction to the language from last lecture, defined as

Our proof will be by contradiction. In particular, this means we’ll assume that is decidable, then derive our contradiction by giving a decider for .

Thus assume that is decidable. This means there is a Turing machine which decides . This tells us that for every pair , we have if and only if halts, and if and only if does not halt.

We’ll use to build a Turing machine which decides . For any , define as follows.

-

- Set .

- If , then output 1.

- If , then set .

- If , output 1.

- If , output 0.

Since is a decider, it halts on all possible inputs . Now, if , we know that does not halt, which implies that . So we set in this case. Next, if , we know that does halt. We then test the output of by running it. If , then again we know , so we set . Otherwise, , and thus , so we set .

Thus, halts on all possible inputs, and clearly decides . This contradicts our previous result that is undecidable. Therefore, is undecidable.

Final Remarks on Undecidability

Rice’s Theorem

It would be great if the halting problem were decidable, as it would give us an efficient way to check if programs halt on all possible inputs. However, one may be wondering if there are other properties about programs we can efficiently decide/test. For example, “does this program have at least 5 for-loops?” or “does this program have a switch statement, followed by an if-then-else?” Unfortunately, these are also undecidable problems.

This is a result known as Rice’s Theorem, which informally states that it is impossible to determine if a computer program has any non-trivial property . I.e., the language is undecidable. Here, a non-trivial property is a property which is not true or false for every program (i.e., there are some programs that satisfy , and some which do not).

Mathematical Incompleteness

The idea of undecidability (and uncomputability) is closely related to (and inspired by) Gödel’s incompleteness theorem. In the early 1900’s, there was a large push to establish a set of mathematical aximoms from which you can prove or disprove any mathematical property. However, Gödel proved this is impossible. He showed that no matter what set of axioms you choose, there will always be theorems you cannot prove or disprove. This actually inspired the results on undecidability/uncomputability, and is closely related to these ideas.

Time-Efficient Computations

We’ll now turn our focus to a central topic in complexity theory: defining classes of efficient computations. This leads us to defining and discussing various complexity classes. Informally, a complexity class is simply a set of languages which are decidable (resp., computable) within some resource bound. Example resource bounds include running in linear time, running in logarithmic space, etc.

Deterministic Time

Building towards what we as computer scientists consider efficient, we turn to time bounds. We’ll define the notion of deterministic time.

Definition. Let be a function. A language is in the class DTIME if and only if is decidable by a (deterministic) Turing machine in time .

All Turing machines we’ve discussed and defined so far have been deterministic. These machines all have straight-line computations: they execute their transition function, which simply outputs the next state. Later, we’ll see non-deterministic Turing machines, where the transition function can output a set of possible states and the Turing machine non-deterministically decides which state to pick next.

The Complexity Class P

Given the definition above, we can now define the set of (what we consider to be) all efficient computations. This is the complexity class P (which stands for polynomial).

Definition (P)

We consider anything computed in polynomial time (with respect to the input length) to be efficient. Examples of problems/languages in P include:

- Graph connectivity

- Digraph path exists

- Checking if a graph is a tree

- Integer multiplication: does ?

- Are the integers and relatively prime?

- Gaussian elimination over rational numbers: For matrix and vector , does there exist such that ?

Discussions on P

Does the computational model matter?

We’ve defined P with respect to -tape Turing machines. But, as we’ve seen, -tape Turing machines are equivalent to all other Turing machine models we’ve seen, including RAM Turing machines which reasonably emulate real-life computers. Moreover, the “equivalence” here is that all machines can simulate all other ones with at most polynomial overhead in the runtime. This means all of these computations still fall within the class P.

In fact, many people believe that Turing machines can simulate any physically realizable computational model or system. This is known as the Church-Turing thesis.1 Some people also believe in the strong Church-Turing thesis, which states that this simulation can be done with only polynomial overhead in the runtime. However, as we get closer to quantum computing being physically realizable, people may stop believing in this since, for now, we do not know of a way to simulate quantum computations on standard Turing machines with only polynomial overhead.

Why polynomial time?

It is certainly true that an algorithm running in time is impractical starting at ; yet this is a polynomial. Why do we consider all polynomial time algorithms to be “efficient?”

One reason is above: the Turing machine is polynomially-equivalent to pretty much every model we have thought of, so it makes sense that polynomial time should appear somewhere in what we consider to be an efficient computation. Polynomials also compose well, which emulates how we compose computer programs. Often, computer programs will run sub-routines, and will run routines one after another. If all these runtimes are polynomial, then the final runtime remains polynomial as well. This is since for two polynomials and , the functions , , and or are all still polynomials.

Another reason is historic and heuristic. Often in history, someone is able to solve a problem in polynomial time, but for some large polynomial like . But this algorithm is later improved to a more reasonable polynomial, such as or .

Finally, polynomial-time problems are roughly equivalent to most (if not all) problems that we can efficiently solve on modern computers.

Worst-case time complexity is too restrictive

If you have a problem where for of the inputs you have an algorithm, but for you have an algorithm, then we’d say the algorithm runs in time . In particular, we keep P as a worst-case class. Some argue that this is too restrictive, which is valid. However, often it is much simpler to construct an algorithm that can solve all problem inputs in some amount of time, rather than trying to enumerate (the possibly infinite amount of) the inputs which have better algorithms.

This criticism of P is also addressed in complexity theory itself via the introduction of alternative models and classes, including approxmiation algorithms and average-case complexity.

Decision problems are too limited

We’ve framed P as a class of decision problems, but often we actually want to find solutions to these problems. This is known as a search problem, where you are asked to find an answer rather than decide if something is true or false. An example of this is: instead of deciding if there exists an such that , you just compute the solution . It can also be difficult to frame search problems as decision problems in the first place.

However, most often it is the case that the difference between search and decision problems is, again, only polynomial. That is, we often can solve a search problem when given an algorithm that decides the equivalent decision problem, only costing us polynomial overhead in the runtime; the reverse is often true as well.

Time-Efficient Verification of Problems

Sometimes, we don’t want to solve problems, but would like to verify solutions when given an answer. Moreover, this verification should at least as efficient as solving the problem itself.

Suppose we are given a large integer and would like to find the prime factors of , which we denote as . We believe it to be difficult to find given just . However, if someone gives you some numbers which are claimed to be the prime factors of , there is a simple and efficient algorithm to verify this is true.

- Check that each is prime.

- Check that .

Clearly (2) is efficient, only requiring integer multiplications. A relatively recent result showed that (1) is also efficient and doable in polynomial-time. So verifying that is the product of is also efficient.

Efficiently Verifiable Languages

This gives us a new way to define languages: efficiently verifiable languages.

Definition. Let be a language. We say that is efficiently verifiable if there exists polynomials and , and Turing machine running in time such that

In the above definition, we call a verifier, the instance, and the certificate or witness.

The Class NP

The above new notion of languages gives us a new complexity class: NP.

Definition (NP).

P vs. NP

We widely believe that . In fact, we build many systems (e.g., cryptography) based on the above assumption. Resolving this either way is one of the [Millennium Prize Problems](https://www.claymath.org/millennium-problems/).However, we do know one thing for certain.

Theorem 3.1. .

This is true since every problem in can be decided in polynomial time with no witness/certificate. So it meets the definition of efficiently verifiable.

Non-deterministic Turing Machines and NP

There is an alternative definition of the class , which utilizes non-deterministic Turing machines.

Definition. A non-deterministic -tape Turing machine is identical to a (deterministic) -tape Turing machine, except for the following modifications.

- The transition function of the non-deterministic Turing machine is defined as , where denotes the power set operation.2 During any step of the computation, the transition function outputs a (possibly empty) list of next possible Turing machine configurations.

- Given a list of next possible configuration from the transition function, the non-deterministic Turing machine non-deterministically chooses the next configuration to execute from this list.3

Intuitively, deterministic Turing machines (the ones we defined in Lecture 1) are “straight-line”: every step of the computation proceeds directly from the previous one. For non-deterministic Turing machines (which we’ll denote as NTMs), they look more like “branching” programs: at every step of the computation, the Turing machine has a set of possible computational paths to head down, and non-deterministically chooses the path to proceed down.

How do we define decidability of a language with respect to NTMs? At first, it may seem difficult since there are many possible paths an NTM can do down during its computation. But, the answer turns out to be simple: we require all computational paths to halt, and there to be at least one accepting path (out of possibly exponential) which correctly outputs the decision.

Definition. A language is decidable in time by a non-deterministic Turing machine if

- if and only if there exists at least one execution path such that .

- All execution branches halt in time at most for any .

We can use this above definition to expand DTIME to NTIME.

Definition. Let be a function. Then we define to be the set of all languages decidable by an NTM running in time .

Alternative Definition of NP

Given NTMs and NTIME, we can now see the original formulation of the class NP.

Theorem 3.2.

Note that this definition is equivalent to the efficiently verifiable language definition. At a high level, this is because of the following reduction.

- Let be a witness to the fact that (i.e., for efficient verifier ). Then, intuitively, correpsonds to some correct computational path on an NTM which decides .

- Let be an NTM which decides . Then we can specify a witness which is the computational path that takes to an accepting state. The deterministic machine takes this as input and simulates the NTM by following the computational path specified by .

Recall our prime factor problem from before. Let be a large integer, and suppose we wish to find the prime factors of . Then there is an extremely simple NTM which finds these prime factors. Let be this machine. It does the following.

- Non-deterministically choose prime numbers .

- Check if . If yes, output ; else output .

Solving NTIME in DTIME

Currently, until vs. is resolved, the most efficient ways that we know of to solve problems in NTIME using only DTIME computations requires exponential time. Let denote the class

Lemma 3.3. .

Proof. Enumerate all possible branches of the NTM deciding the language (equivalently, enumerate all certificates/witnesses in the verifier definition). Then, run through this list until finding an accepting branch of the computation. If the original machine ran in time , then this procedure runs in time . By assumption, is a polynomial, so we are done.

-

Note this is just a belief and not a formal theorem or conjecture. ↩

-

Given a set , the power set of , denoted as , is the set of all possible subsets of . Notably, . ↩

-

Recall that non-determinism is not the same as behaving randomly. The choice of a non-deterministic machine is arbitrary and possibly not computable. ↩

Lecture 4

In-class notes: CS 505 Spring 2025 Lecture 4

Recall how we have the notion of a universal Turing machine: a machine that can simulate and solve any problem that any other Turing machine can solve. We’d like to now define a notion that is similar to this where, if you can solve one problem efficiently, then you can use that algorithm to solve a different problem (also efficiently). This leads us to the notion of reducibility.

Reducibility

As above, the idea of reducibility is that if I can solve problem (i.e., decide the language ), then I can use to solve (i.e., decide) a different language . Moreover, this is efficient: there is only a polynomial overhead in using to solve .

Definition (Polynomial-time Reducibility). Let and be languages. We say that is polynomial-time reducible to , denoted as if there exists a function that is computable in polynomial-time such that

Note that in the above definition, it is saying that if we can solve , then we can use to efficiently solve . This notation can be confusing to some people (I myself dislike it), so just be aware.

Lemma 4.1 (Reducibility is Transitive). Let , , and be languages. If and , then .

Proof. By definition, there exist functions such that

This implies that . Note that both and are polynomial-time computable, so the function is computable in polynomial time.

Since reducibility is efficient, it immediately tells us that if one of the problems is efficient, then the other is also efficient.

Theorem 4.2. If and , then .

NP-Completeness

NP-Completeness captures the ideas and goals we’ve been building so far: problems in NP that if we can solve, then we can solve any other problem in NP.

Definition (-Completeness). Let be a language. We say thta is -complete if

- The language is in : ; and

- The language is -hard: , we have .

Notice that there can be languages such that is NP-hard, but this would not be NP-complete, unless or (which we don’t know is true or not). NP-completeness captures the intuition that if we can use a language to efficiently verify every other language in NP, then this language itself should be efficiently verifiable (otherwise we just verify the other languages directly).

Unhelpful/Useless NP-Complete Language

We’ll now see an example of an NP-complete language which is not helpful for solving problems. This is because, as we’ll see, it is intimately tied to the Turing machine.

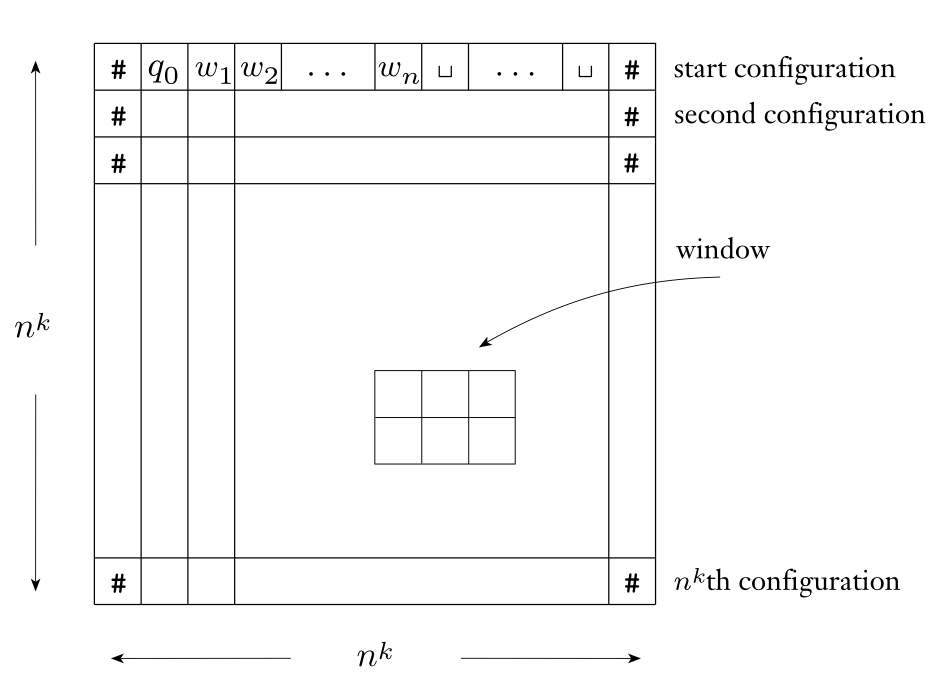

Denote by the language of all satisfiable Turing machines, defined as Here, and denote a string of (resp., ) 1’s. This is a syntactic convention we use to ensure that any machine deciding runs in time that is polynomial in and ; whereas if we specified and in binary, then the machine would only run in polynomial time with respect to the bit-length of these numbers.

Lemma 4.3. is NP-complete.

Proof. Clearly by definition. The NTM deciding takes the input , guesses the string and runs . If exceeds computational steps, output ; otherwise, output according to ( if , if ).